An interview with Metahaven

The work of Metahaven encompasses filmmaking, writing, and design.

Their films include Capture (2022), Chaos Theory (2021), Hometown (2018), and Information Skies (2016), nominated for the European Film Awards 2017. Their books include Digital Tarkovsky (2018), and Uncorporate Identity (2010, edited with Marina Vishmidt).

Metahaven has presented solo exhibitions at MoMA PS1, New York, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, ICA London, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, Asakusa, Tokyo, Izolyatsia, Kyiv, e-flux, New York, Tick Tack, Antwerp, and State of Concept Athens, among others, as well as participated in group exhibitions at Artists Space, New York, the Museum of Modern Art Warsaw, the Gwangju Biennale, the Sharjah Biennial, the Busan Bienniale, Ghost:2561, Bangkok, and many others. Metahaven are heads of department at the Geo-Design MA at DAE, artistic advisors at Rijksakademie, and affiliate researchers at Antikythera.

Anna Winston: Congratulations on your new role!

Metahaven: Thank you! We’re really excited, to be honest. Though these are challenging times, we feel Geo-Design could hardly be more relevant than today.

AW: What are your plans for the Geo-Design MA as its new heads?

MH: We wish to explore a few questions. These are: how can design be a neighboring discipline to ecology, geology, biology, physics, technology, geopolitics, and cognitive science?

This probably sounds really ambitious. We don’t expect to have all the answers already.

And how can the research, narratives, experiments, ideas, poetics, and solutions that emerge from this adjacency be brought into the world collaboratively?

Some kind of research question guiding the design process is important. Some element of fieldwork and primary research, too. The students at Geo-Design have broad research concerns, indeed ranging from ecology to geopolitics and further. They are united perhaps by an interest in understanding complexity through focused case studies.

And, importantly, there are aesthetics; not to be missed as an element of how design interfaces with the world, how it makes things feel.

AW: What is your vision for the evolution of the course?

MH: A design MA generally has a dual purpose. On the one hand, it deepens one’s involvement in a professional field. On the other, it questions and unsettles that field. One of the objectives of Geo-Design is to help create new practices in which design is capable of formulating and answering questions it didn’t ask before. More colloquially, we want students to be both challenged and happy in their studies, and we want them to graduate with beautiful, rich work that asks questions that can drive the next phase in their professional work, and help them interface with wider networks of practices outside of design.

AW: How does your teaching relate to your practice?

MH: It is part of our practice.

AW: What is the biggest lesson you have learnt so far from your students that has impacted your own work?

MH: The biggest lesson one can learn from students today is surely ethical. Current students face a world that’s looking very different from the 20th and early 21st century periods in which design as a discipline developed and solidified. That’s no reason to ditch everything that was built so far. But the different situations we face today are one reason for a renewal, or a reconnection to foundational issues, or, as the DAE says, “designing design.” What we can learn from students is how to intuitively establish an ethics in doing so—an ethos all of their own. The students do sense the world they want to live in and will shape their practices accordingly. This deserves massive respect.

AW: How would you describe what you do, and has that changed over time since you began working together as Metahaven in 2007?

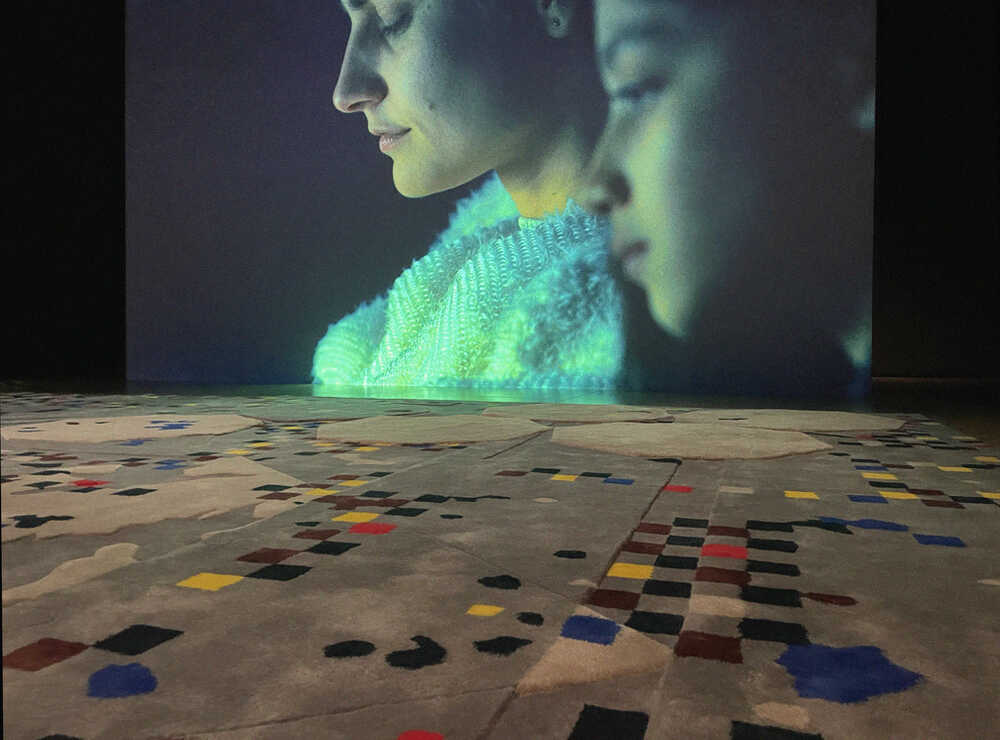

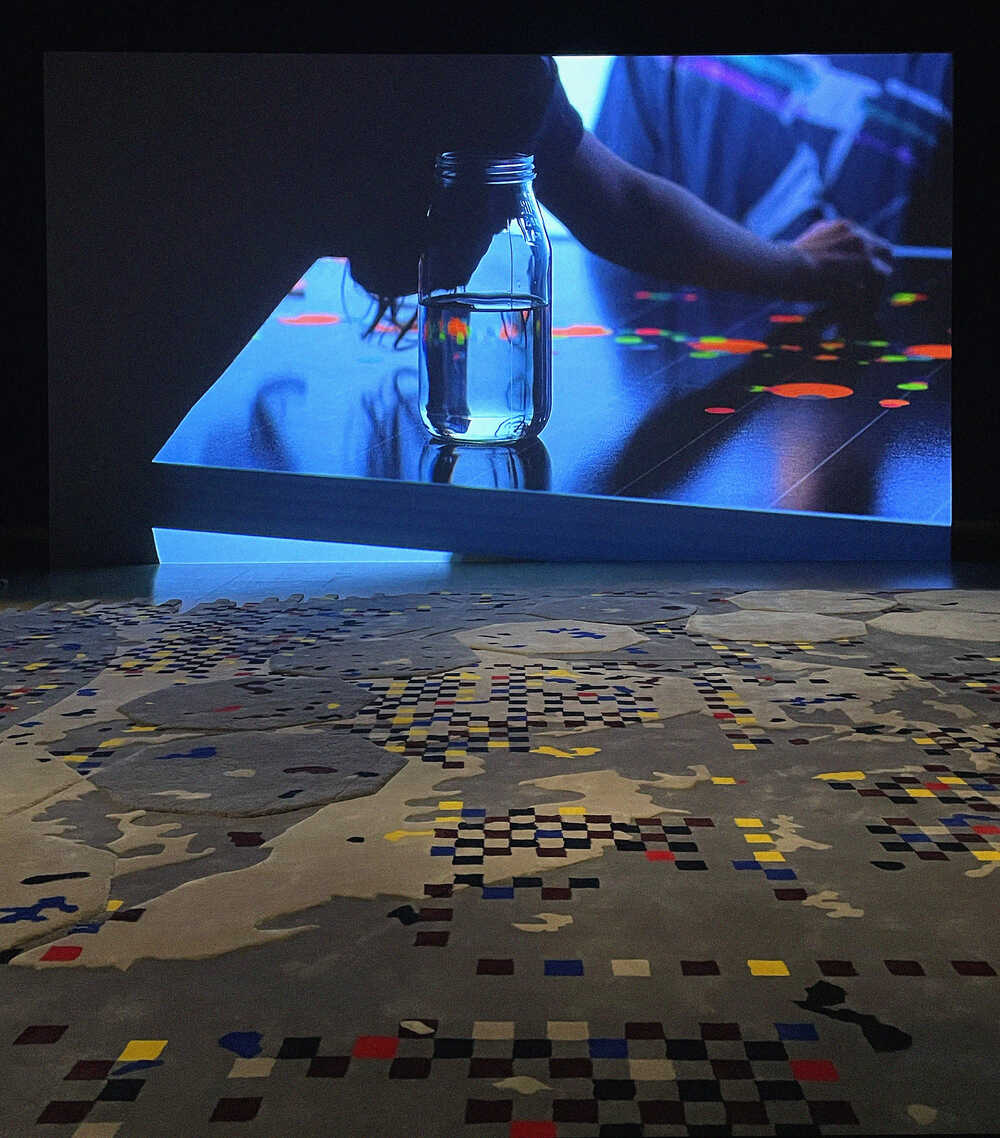

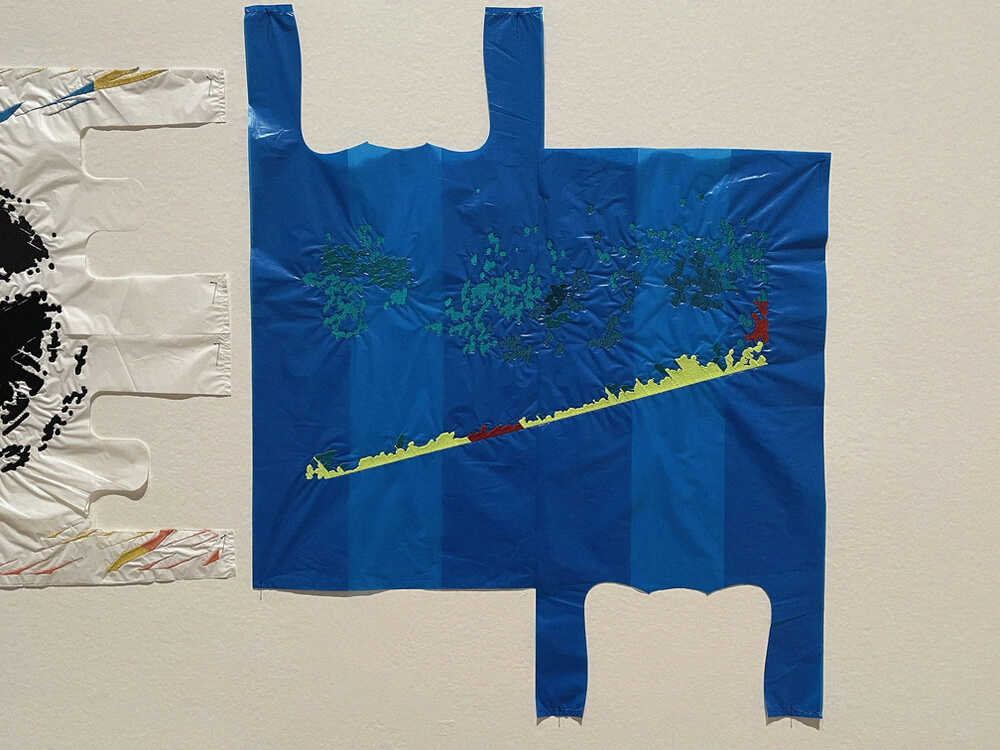

MH: We are an artist collective working in filmmaking, design, and writing. Our work evolved from graphic design. We make films, write books, create textile pieces, and we still do graphic design as well, around commissions that sometimes involve speculation or hypotheticals. Interdisciplinary research questions have always driven our practice, but we’ve also felt the need—at various moments, in fact—to reorient the questions we asked ourselves and evolve the focus of our work. The Feeling Sonnets (Transitional Object) is the film we are currently working on. It’s about poetry and AI, and based on a poetry collection by Eugene Ostashevsky. Our new book, on the future of the beholder’s share in art, is scheduled to be out with Verso in Spring 2025.

We would like to mention two elements of our practice that we hope to bring to Geo-Design. One is about the connections between art and science. The other is about moving image and cinema as research tools. Art and science relate, and don’t. Everyday sensory experience and fundamental facts of nature—like the ones found in quantum physics, for example—go together and don’t. Design, like art, is very much tied to sensory experience. But, for example, the fundamental interactions between subatomic particles seem to defy some of the basic beliefs that we hold about the physical world based on our everyday experience. And we can extrapolate this to a larger issue of complexity. As design confronts complex systems—systems that often aren’t what they feel like and don’t look what they are like—in what ways can we and can we not trust our everyday and our sensory impressions, knowing and holding on to the fact that we are still bound to these experiences?

Also, moving image and cinema can be a research tool. That’s the other element from our practice that we love to bring to Geo-Design. It doesn’t mean that filmmaking is mandatory at Geo. Not at all. In fact, we don’t believe in the idea of a monolithic “film department,” especially not here. But the research possibilities and objecthood of do-it-yourself cinema and moving image could be taken more experimentally and treated more extensively, just like other forms of materialization. DAE is the perfect place for this as it doesn’t yet have a long tradition in moving images, but it has a huge tradition in materialization. It is from the notion of materialization that our predecessors at Geo-Design, Formafantasma, led the department to its initial critical stance.

AW: You launched your practice in the wake of the Dutch Design phenomenon of the ‘90s and early 2000s – how do you relate to that idea of design (if at all)?

MH: To be honest, not so much. We don’t think that design should be named after a nation-state.

AW: How does this relate to the idea of authorship or the designer as auteur – Is that idea even still relevant? Would you encourage students to work collectively? Are there any downsides to this approach?

MH: The phrase “the designer as {…}” needs to be let go of, we feel. Not so much the part that asks for a personal vision. The part that needs to be let go of is the “as” in the sentence; the idea that any non-design within design is a change of hats and a departure from design. It is only because design has previously tried to define itself as a singular, discrete discipline—with an internal, professional knowledge system that’s completely separate from other disciplines—that the need to defend a singular, monodisciplinary “designer” has emerged. Whilst we do not agree with this idea of the core model from which everything else is a deviation, we do need to stress the continued importance of craft and making which are also part of this core. We’re quite interested in what designers are thinking about while they make, and research in design was probably first born from there. At least in our case, it was. We would like to think a bit more about the idea that being a designer brings one in contact with many things that are not design, and that these things both affect and effect the designer towards something they at first were not, or at least not by training. That, in turn, makes design evolve.

Education is a space where these directions reach a certain tension, as of course, educating people to be “anything they want to be” is not something that anybody can seriously believe in. So, how may one begin to define the constraints?

Geo-Design is one way of defining constraints, towards a certain range of research interests, questions, and concerns that can also be expressed as values, as urgencies, as needs, as politics.

As Sean Canty, Zeina Koreitem, and John May have recently suggested in Harvard Design Magazine, the idea of a “multihyphenate” practice captures some historically strong notion of what design can be, and this idea appears to be inherently between things. It appears to inherently consist of positions, interests, and affiliations woven together by dashes or hyphens. In this multihyphenate logic, we do not need to see design that’s acting in an interdisciplinary way as a change of roles or hats.

Authorship in design is not at odds with the notion of collectivity. Rather, collective work is, in our view, a more advanced version of individual authorship. So yes, we do encourage students to work together, as we encourage them to find their voices as people—another key point of taking time and space to study.