Will the Metaverse Equalise Education for Design Students?

Design education, in my experience, asks a lot of students. Long and intense workdays, the pressure to buy expensive materials and my personal struggle with health and money made me doubt for a while if I would ever graduate. From my point of view, equalising design education would mean creating the circumstances that make it possible for students with less privilege to join, stay, and feel welcome.

Thus, I went into the second day of talks at DAE’s first Research Festival – themed around the idea of the Metaverse and its various possibilities – with one question on my mind: Will the Metaverse equalise education for design students?

After attending and taking in a lot of information, I have realised that the short answer is a definite NO. Let me elaborate…

Impressions from the Research Festival

As Wenting Cheng talked about student-centred education, which uses feedback to improve courses, I started wondering what such a course might look like at Design Academy Eindhoven. She spoke about working with MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses), online classes, and offline classes, about how contributing online would encourage students to engage who usually wouldn’t speak out, and about how to design courses that would interest students and prepare them for the ‘real world’.

Ilse Meulendijks and Annika Frye later commented on this notion of the ‘real world’ in a panel discussion. Not basing research on impressions of ‘the real world’ can open doors, they said, adding that ultimately, the goal of design shouldn’t be generating profit. In this context, I would argue that DAE has prepared me for the real world, as no other institute could ever have.

During her lecture on power structures in digitality, Dr Bianca Herlo said something that struck home. Herlo argued that systems take a shape because we want them to be a certain way, rather than forming ‘naturally’.

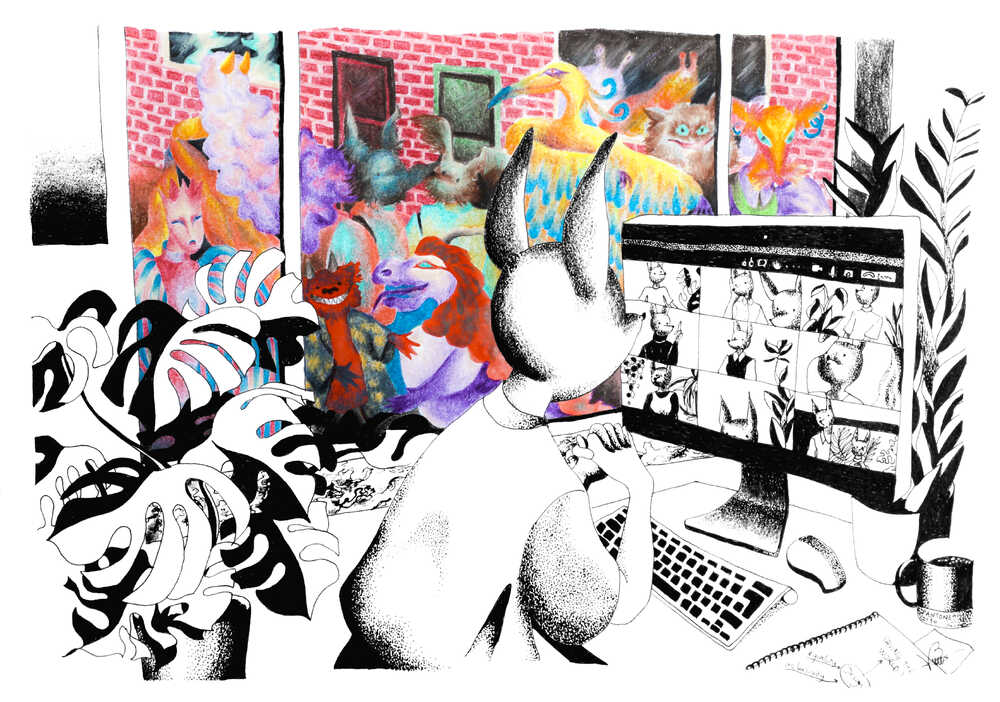

I thought about the systems of Design Academy Eindhoven. The hierarchical systems that influence who gets to join, stay and ultimately feel welcome. The power structures between teachers and students. The differences between formal statements promoting equality and the reality of lived experiences. The largely white, largely cis, largely wealthy, largely able-bodied student body.

In a weird way, it feels ironic to talk about equality here, or diversity, or power structures. I would argue that DAE has prepared me for the real world. A real world of design that is largely white, largely cis, largely wealthy, and largely able-bodied.

Experiences of the last three years

Imagining my dream hybrid education, I think back to the plethora of experiences I had at school over the last three years. In my first year, I would have slept at DAE if that would have been possible. I would have dragged one of those big black tables over me like a blanket of wood. My bed would have been cardboard scraps and discarded drawings, my bedside decorated all over with white cardboard models. My diet ZBar, my entertainment books from the library. In the mornings, I would have washed in the gender-neutral bathrooms, brushed my teeth, stowed my belongings away in my locker, and walked up to Zbar to start the day with a Pain au Chocolat, a large filter coffee and a view that makes you feel on top of the world. In reality, I was lucky to have a house. Every year more and more students start the year homeless or find their homes in campers and on friend’s couches.

Then the pandemic hit in March 2020, about two years ago, and we went online.

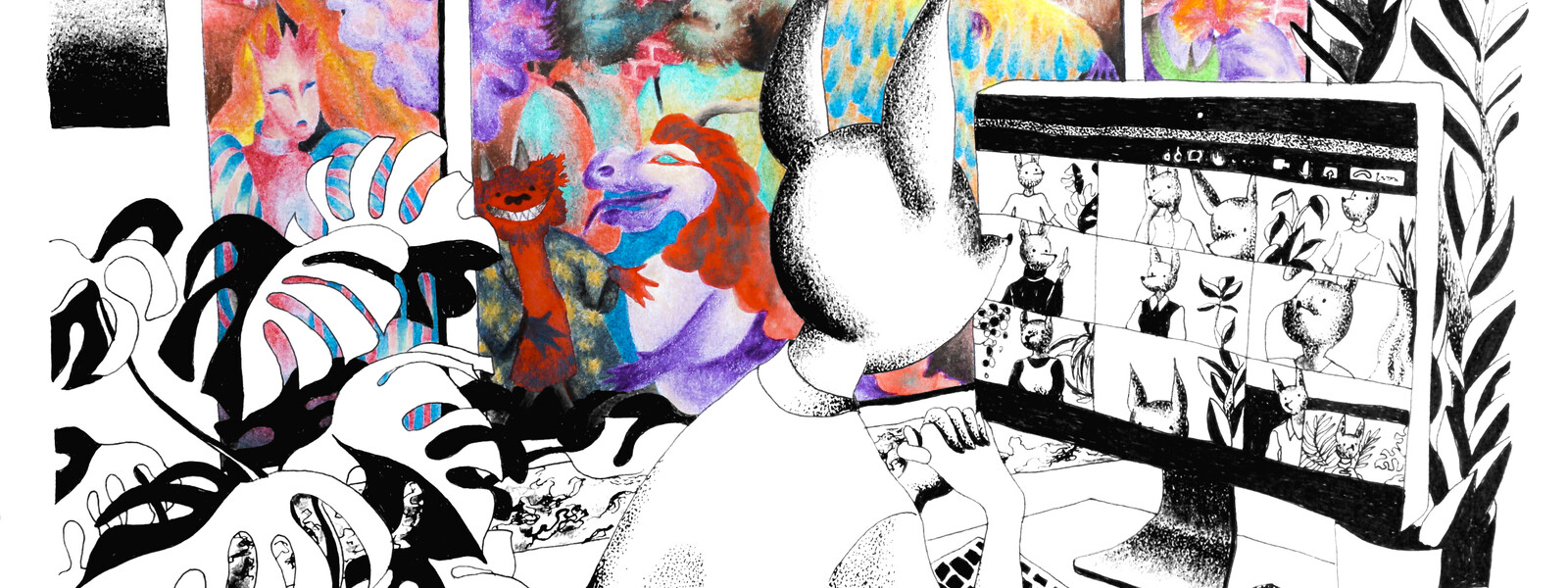

Of course, we can’t compare the Metaverse to Microsoft Teams, but the experiences of the student body and teachers over the last two years can give us valuable insight into what online education can offer and what it lacks. Personally, as a chronically ill person, I experienced online education as a great opportunity to attend more school without crossing the boundaries of my own body. At the same time, I had a terribly hard time separating school and my private life — especially once it all happened in the same (online) room. For me, this resulted in never-ending work days, which were just interrupted for food and sleep. This wasn’t sustainable at all.

Besides my personal experiences, I have more general concerns with online education:

- Our design education right now is heavily focused on materiality

On one side, the Metaverse and digital education could offer a new understanding of what materiality is. Do we need something to exist offline to be considered real? Sculpting objects in 3D could offer an opportunity for us to waste less and to be on the cutting edge of developments that are happening technologically right now. At the same time, the tactility of wood and clay and metal is what drives so many of us. We don’t think only with our minds, but with our hands.

- Studying design is expensive

To access the Metaverse, students would need pricey equipment. The materials we pay for already aren’t affordable to everyone. Some recent internal initiatives have made it a lot more accessible, but I can still remember having to choose between food or material in my first year.

- What if people don’t want to join online?

Everyone has their fair share of horror stories from the last two years. From teachers that suddenly have to teach to a room of black squares, not quite sure whether anyone is there or listening, to students who suddenly had to DIY their education because teachers didn’t want to call online. Not to mention, in online spaces, concentration spans can reduce horribly.

Perspectives on the future

If I understood one thing from the talks at the Research Festival, it’s that the Metaverse isn’t as ‘around the corner’ as I thought it was. Even though DAE has its own cutting-edge local Metaverse now, most of us do not have access to the kind of equipment needed to follow a lecture there.

What is already here and is relevant today are conversations around equality and equity within design and design education. During her talk, Dr Bianca Herlo quoted Ruha Benjamin: “It is people who imagine our technological infrastructure. The fantasies of some are the nightmares of others.”

Our technological infrastructures are imagined by people, and our current systems are too. We urgently need to take the steps to make sure that the future equivalents of our current systems will be more equal.

So, what could equality mean within a school like DAE?

Equalising design education would mean creating the circumstances that make it possible for students with less privilege to join, stay, and feel welcome.

Right now, as stated above, our student body — and teaching body — is largely white, largely cis, largely wealthy, and largely able-bodied. If we imagine a more equal future, it is important to consider how we can make our school an environment that is less hostile to people that fall outside of this homogenous demographic.

We should listen to the voices of the people within our school that are already advocating for change. We should listen with empathy and understanding, not only because it is the right thing to do, but because design becomes irrelevant when it is used to only share one predominant narrative.

Designers that are positioned outside of this narrative don’t need us. We need them.