Herman Kuijer

Herman Kuijer is one of the Netherlands’ leading lighting designers, known for installations that place public interaction at the forefront of the visual experience. After his graduation in the 1970s from Design Academy Eindhoven, he returned in the 1990s as a professor and coordinator in the BA and MA faculties, alongside maintaining his practice.

Kuijer spoke to writer, curator and DAE alumnus Tiiu Meiner about his experiences of learning and teaching at the Academy, and offers words of advice shaped by a career spanning five decades.

→Tiiu Meiner: You arrived at the Design Academy in the 1970s, when it was still a very small and unknown place. What attracted you?

Herman Kuijer: It was a kind of romantic and very intuitive feeling. I did not want to follow in the footsteps of my family’s business, and by coincidence I learned about the Academy. At the time there were three departments, and I intuitively chose the textile department. Even though I wasn’t so interested in the materiality of textiles, the mentality, the freedom of spirit and the mindset was appealing to me. The department was not solely focused on typical design problem-solving, but rather on questioning design and the status of life, and innovating. As a student, you were able to develop your own path. I think the mentality in the former textile department formed the basis of the design methodology and practice of what DAE stands for today.

→TM: What was the most challenging factor during your time at DAE? Do you think a lot has changed since that period?

HK: When I started in 1972, the global environmental publication by The Club of Rome came out. Their message, with an image of a globe that was melting like a candle, made it clear that we could not continue consuming as we were. The current status of the world proves that their message was very relevant then and also now. 50 years later we can see that they predicted exactly the climate change that we see today.

But somehow, my generation stopped addressing these issues, and it’s unclear why this climate crisis went to the back of our minds for so long. I don’t know why, but collectively for us all, the discussion faded away. To this day, I am surprised this alarm did not go off earlier for my generation. I still think ‘Why did that happen?’

→TM: Did your perspective of DAE change when you returned as an educator and professor?

HK: As professors, we were looking for a methodology that could create a space for each student to practice to the utmost of their abilities and spaces to develop themselves, including unorthodox experiments with materials and concepts. There was no general model where each student should fit in. As a professor, I tried to give trust and strength to students to perform and develop themselves within an autonomous context.

→TM: What brought you to the medium of light as a designer?

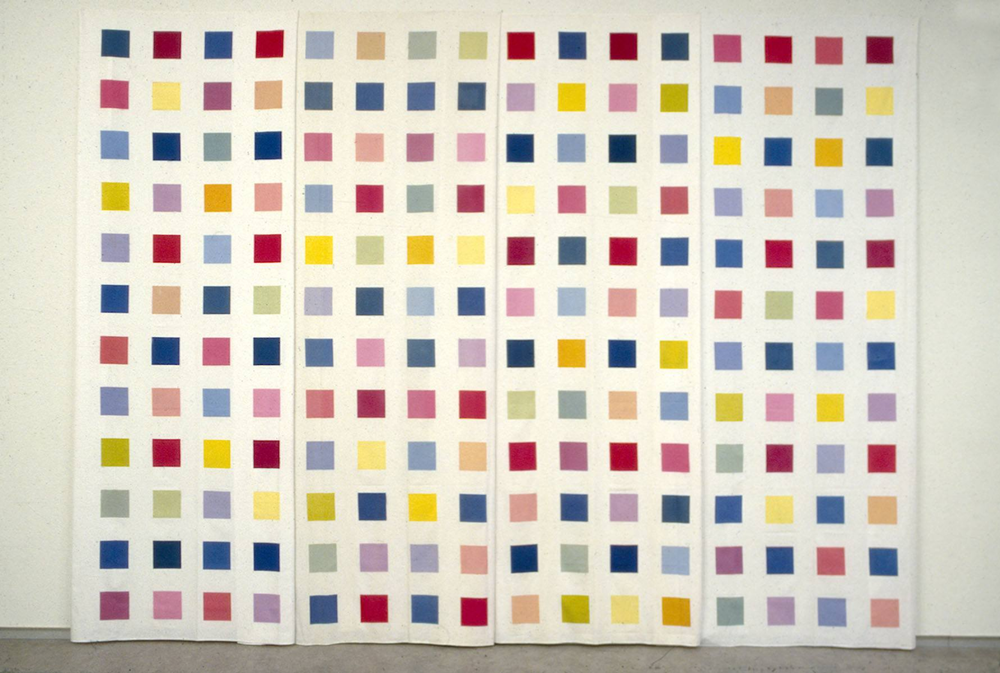

HK: Still inspired by the Club of Rome, I always thought ‘I don’t want to make more useless objects’. I wanted to make something that had an urgent need and meaning. I also wanted to be able to develop and produce the work myself. My graduation projects were the starting point for reaching that goal. So I started experimenting in the textile department with light and silkscreen printing. Light as a material was unseen in the textile department at that time, at least in the way that I used the silkscreen technique. In an interior space, textile is often used as a visual barrier. While experimenting, I found light can work similarly. Think of the winter sun and how it can create blinding barriers.

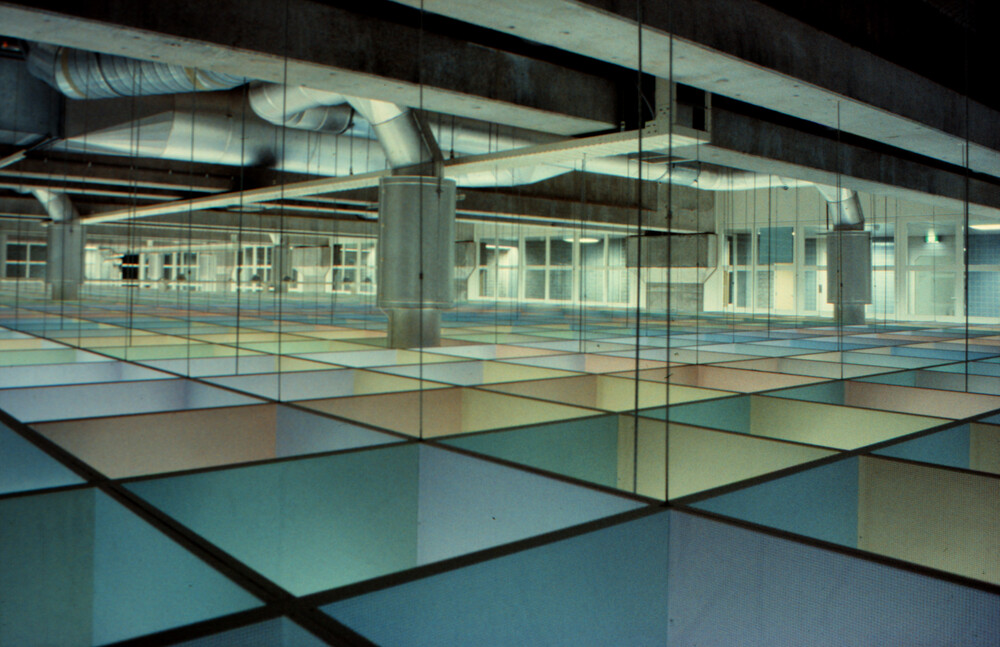

After graduation, I got in touch with Post NL [the Dutch postal service], which was one of the biggest commissioners in those days in the field of art in public space. I created a sculptural, acoustic colour installation for one of their new, large expedition centers in the 1980s. There is a direct relationship between my graduation projects and that installation. Till today I benefit from the research I did during my study.

→TM: Your work is often based on combining interventions in both architecture and public infrastructure – how do you position yourself as a designer towards architecture and urbanism? What is important to you in these spaces?

HK: Most of my creative projects are public commissions, where both architects and designers are invited to come up with solutions. So I always end up working on projects that have a layer of functionality and aesthetics at the same time. That means that there are more layers: community commitment, technical sustainability, deliberate destruction and safety are key issues to deal with. Scale is another important layer in the artistic commissions I engage with. For example, my recent public commission was for an architectural installation of 80 x 80 x 25 meters for the depot of The Rijksmuseum.

I always think of the red and blue Rietveld chair. It looks like a chair, but it is not a chair at all. It’s a sculpture that allows you to sit on it. My lighting work is somewhat similar. Functionally it’s urban lighting, implemented in the infrastructure of a city, but it also acts as a light installation and social sculpture. In the end, it’s about answering those design questions that improve public spaces and create both functional and safe, attractive spaces.

→TM: What advice do you give to the next generation of young designers?

HK: You don’t need to know everything, but you do need to know where to find people that can help you out. You have to find a way to find the things that you don’t know. Know your limitations and know that someone can widen your limitations through collaborations.

Focus on asking yourself the right questions. And don’t forget where you started, like my generation, which more-or-less forgot about The Club of Rome.