Kuang-Yi Ku

Working at the intersection of medical technology, bio-art, and design, Kuang-Yi Ku graduated from Design Academy Eindhoven in 2018. His graduation project – the Tiger Penis Project – applied a non-western perspective to speculative design, looking at how traditional Chinese medicine could be a threat to endangered species that are hunted for ingredients and how synthetic biology might be used to create artificial animal parts.

With his prior education in dentistry and communication design, Ku has developed a unique practice that invites the public to engage in dialogues that explore the future of medicine and the impact of science on our perception of humanity and the future of medicine in society. He is currently pursuing a PhD at Sheffield Hallam University in the UK, further expanding his expertise and knowledge.

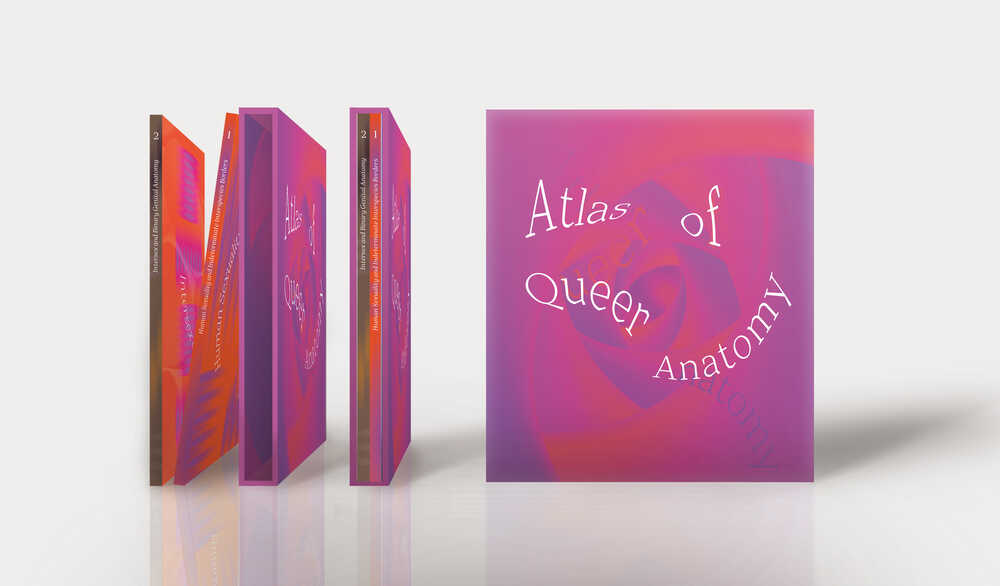

His most recent project Atlas of Queer Anatomy, has earned a nomination for the Design Research Dutch Design Award 2023 adding to an already extensive track record of achievements and accolades. Ku spoke with independent curator, writer and DAE alum Tiiu Meiner about the methodologies that he has developed for working with medical and scientific communities.

→Tiiu Meiner: You work at the intersection of science and design. Can you explain why an interdisciplinary collaboration is important to you?

Kuang-Yi Ku:: Design can be used as a tool for science communication, but in my collaborations with scientists, I try to bring a sense of criticality to the partnership. It’s not just about using design to communicate science but also about incorporating critical thinking and design methodologies into the scientific process.

For example, if I collaborate with a biologist who is conducting genetic modification research, they may struggle to effectively communicate the complexities of GMOs to the public. In such cases, I can bring my design expertise to the table and propose ways to materialize and exhibit the cultural implications of genetically modified foods. By creating models or artefacts, we can engage the audience and create discussions about accepting or rejecting these future foods.

The information and data collected from these interactions can also be used by the scientist for future research or when seeking government support for funding. So working with designers not only helps popularize science but also benefits scientific research by providing alternative perspectives and potentially getting future funding…

→TM: In your opinion, what role does design play in challenging cultural taboos, and how does science complement this process?

K-YK: Design has the ability to visually represent and bring to life certain emotions and desires that are typically challenging to explore through scientific research. The issue with scientific research is that it is usually limited in its ability to address or investigate cultural issues. Science is traditionally based on rational thinking, statistical analysis, and quantitative research methods, which make it difficult for that field to grasp or address the complexities of cultural issues.

Design provides me with a good methodology and approach for exploring and studying these topics then. It allows me to materialize and create artefacts and visuals that serve as cultural probes, bringing the insights of science to the general public. Through design, I can bridge the gap between complex scientific concepts and the perspective of humanity in society. This, in my view, is the power of design

“Through design, I can bridge the gap between complex scientific concepts and the perspective of humanity in society”

→TM: How do you approach the process of identifying and selecting cultural taboos to focus on in your projects?

K-YK: The starting point for my work is usually inspired by my personal experiences and scientific news. Being part of the queer community as a gay man, scientific or medical news related to gender or sexuality has led me to many of my projects. When new technologies in medicine like AI, artificial reproduction, genetic modification, or human cloning are published, people tend to have diverse opinions and disagreements. That often resonates with my personal experiences, and I find inspiration in these areas.

TM: What ethical considerations do you take into account when working on projects that challenge cultural taboos? How do you ensure the well-being and respect of the communities involved?

K-YK: In my practice, I enjoy incorporating irony into my projects to add a touch of humour and subversion. I use the power of irony to challenge rigid patriarchal systems within society. But it’s a fine line – if we approach these topics too lightly, people may miss the point, or if we take it too far, we may contribute to the derogatory discourse. It’s about finding a balance between maintaining ethics and creating a sense of confrontation that challenges social norms.

“I use the power of irony to challenge rigid patriarchal systems within society. But it’s a fine line…”

→TM: What are some potential limitations or challenges you face when bridging the gap between science and design in your projects?

K-YK: The first challenge is usually the learning process. I need to learn a substantial amount of information about the topic during each of my projects. The second challenge is collaboration. The design outcome can really differ from project to project, and I am not an expert in all design outcomes. So, I also need to collaborate with various creatives from different backgrounds and integrate the creative team with the scientific team. That means multiple layers of collaboration and includes not only creative brainstorming but also administrative and financial tasks.

TM: Do you have some advice for young designers wanting to work at the intersection of design and science?

K-YK: Be open-minded, and don’t be judgemental about the different mindset that exists in these two fields. Be ready to accept that collaborating means you may have to have a discussion about issues that scientists might have a very different approach to. Also, don’t get discouraged but stay passionate about approaching scientists. You might receive a lot of refusals, but you should keep insisting on explaining your passion. There is a chance that you will eventually be understood and have the opportunity to collaborate.